As one year transitions to another, it is our custom to share with you a series of reflections on the milestones and tectonic shifts in our understandings of the world that have marked our lives over the past year.

Contributions

- On Transitions Alan Brown takes stock of a year of difficult, necessary, and hopeful transitions.

- Planning Ahead for Organizational Transitions John Carnwath discusses how organizations in Canada are proactively managing lifecycle transitions, and how we might want to follow suit.

- Transitioning Roles Erin Gold reflects on her tenure with WolfBrown and shares a bit of advice.

- Returning to Communities of Practice Kathleen Hill rediscovers the value of human connection through in-person convenings.

- Collaborating Towards a Responsive Model Alan Kline notes a hopeful trend in the ways arts organizations are collaborating more closely.

- Transitioning From Treasure House to Tool Box Dr. Dennie Palmer Wolf shares how her work with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art provoked fresh perspective on the evolving role of museums in society.

- Leaning into Community: Transitional Firsts in Arizona Surale Phillips shines a light on the Chandler Center for the Arts’ evolution towards inclusion.

- Arts Versus Administration Kacie Willis explains how her new role at WolfBrown brings balance to her life.

- In Memory of Geoff Nuttall Dr. Thomas Wolf celebrates the life of his friend and colleague in the Saint Lawrence String Quartet.

On Transitions

By Alan Brown

My colleagues trace important shifts in their understandings of the world, both personal and professional. They speak of transitions arising from larger trends and shifts in the operating environment – transitions that will reshape us, inevitably. They also speak of transitions that come about through clarity of intent and force of will. These are not inevitable, but transitions born of passion, courage, and foresight.

The transition towards a more democratic culture is not inevitable, but one requiring time, humility, selflessness, and perseverance. It is the defining transition of our work at WolfBrown, in terms of how we work, but also in terms of what we hope to see as a result of our work. It is a journey, not a destination – a long, slow walk towards a brighter day. Dennie Palmer Wolf and Surale Phillips note bright spots in their own journeys down this road, illustrating how our work continually challenges and renews us.

Kathleen Hill writes about the transition back to in-person meetings and the value of sharing the same physical space with colleagues, while Alan Kline highlights a necessary transition towards more collaborative research practices, a transition we are very much nurturing at WolfBrown.

John Carnwath writes about once-in-a-lifecycle organizational transitions and offers hope that they’ll become intentional and not just inevitable. And Tom Wolf, Erin Gold, and Kacie Willis reflect on milestones and realizations that have marked their year.

For the coming year, all of us at WolfBrown wish you the bravery and fortitude to make the transitions that renew your spirit, unleash creativity, and spin gold out of the hay left to us by the pandemic.

Planning Ahead for Organizational Transitions

By John Carnwath

Looking back years from now, we might see that it wasn’t the mandated venue closures and stay-at-home orders –which, while unprecedented in recent memory, were ultimately temporary – that dramatically impacted the arts sector. Instead, the most decisive impact might be the changing priorities and needs in the communities served by arts organizations in the post-pandemic years.

Speaking with arts organizations in Detroit in the first weeks of the COVID-19 shutdown, the most immediate concern was securing quick access to operating support. Still, it also seemed inevitable that there would be a significant need for “Transformation Capital” in the sector within the next year or so. Building on the Nonprofit Finance Fund’s definition of “Change Capital,” we envisioned this as funding that would allow organizations to reinvent themselves through processes such as mergers, restructuring, downsizing, or well-planned, orderly sun-setting that preserves cultural assets for the benefit of the community.

Rapid relief funds, PPP loans, and SVOG grants bought the arts sector some time. However, at the end of 2022, with public attendance still low and accounts of arts nonprofits closing becoming a staple of our newsfeeds, it’s hard to avoid the ominous feeling that the pandemic’s second shoe may slowly be dropping – a gradual drip rather than a sudden thud. A substantial pool of Transformation Capital may also still be necessary to support the sector as it adapts to the new post-pandemic reality.

Our colleagues to the north have been more proactive on this front. Consortiums of funders in several cities, including Calgary, Edmonton, and Toronto, have established grant programs that specifically fund organizational transformations of the type we envisioned, including restructuring, mergers, permanent strategic partnerships, transitions to new business models, succession planning, and even “wind-downs” and “organizational closure.”

Brian Loevner at BLVE Consults has been tracking the developments in Canada, and he generously shared some of his observations in a recent phone call. One of the most interesting outcomes from my perspective is that establishing these funds has encouraged more open conversations about the realities of organizational lifecycles and the support needs of organizations that are going through transitions. It’s also brought a much wider range of options for organizational transformations into view: funded projects have included a merger between a nonprofit and for-profit organization, an independent annual festival that became a program of a mission-aligned year-round institution, and the fusion of a production company and a venue.

Once organizations have reached the end of their line, it will be too late to start thinking about how alternative futures for the organization might have looked. It would be prudent for arts funders in the US to start looking at the lessons learned in Canada and pooling their resources to establish similar programs. If a wave of distressed arts organizations is in fact coming our way, there are important questions to be considered – many of which have significant implications for cultural equity.

- How do we identify assets (physical assets but also programs, networks of artistic collaborators, relationships with community organizations, annual events, etc.) that should be preserved through the transition to maintain the vibrancy of the cultural ecosystem even if the organizational structures change drastically?

- What legal, planning, and financial support will be necessary to ease the transition?

- Might distressed organizations need to enter a form of receivership under the umbrella of a larger institution or foundation while the needs and assets of affected organizations are surveyed and the ecosystem is restructured in ways that are better suited to the needs of the community and the current environment?

Change is difficult, and it’s coming our way.

Transitioning Roles

By Erin Gold

As my tenure at WolfBrown ends and I transition to my next chapter, I want to use this space to say thank you to my colleagues (especially all of you!), all the individuals, and arts and cultural organizations I have had the honor and pleasure to work with throughout these past five years. While I, admittedly, stumbled into the field of arts management and research, I am truly grateful for this time in my career and all it has afforded me to learn. I am leaving WolfBrown as a stronger researcher, thinker, writer, and dare I say, more well-rounded human being.

While this acute change marks a new period in my life, in reality it is simply the latest marker of change in what has come to feel like a constant, years-long transition. Most individuals and institutions alike have been forced to adapt (again, and again, and again) to the world the pandemic has created and continues to create. For many individuals and institutions alike, this forced adaptation has been uncomfortable at best, painful at worst.

Three years in, many arts and cultural organizations are grappling with and trying to adapt to the fact that 20-40% of their pre-pandemic audiences have yet to return. This has led many, if not all, of these institutions to ask the same universal question, “What should we do?!” While this question is a universal one, how arts organizations ultimately answer it, will certainly be unique to them.

However, here is my small piece of parting advice to you: listen to your people. Which is to say, listen to the people that matter to your organization – internally and externally. While this advice may seem counterintuitive (given all you must plan for and do), now is the time when your organization should invest in and listen to what your staff and patrons have to share with you. Our research has shown time and again that they are eager to share their thoughts with you. But for their words to have impact, you as an institution must listen. Let this be the lodestar that guides your organization through this recent wave of transformation.

Returning to Communities of Practice

By Kathleen Hill

Last year, I wrote about the thrill of being able to return to arts spaces as an in-person audience member. I had just finished a weekend trip with a friend to Broadway in early December. We were lucky enough to see Jagged Little Pill and Company with their original casts, and we even managed to fight the crowds to see the Christmas Tree at Rockefeller Center and watch the light show on the Macy’s building. It felt good to be … “normal.”

This year marked another return to in-person experiences: coming together with my communities of practice.

It’s strange to say, but as a young-ish professional, I hadn’t realized how much I was missing out on with my career existing in small boxes on screens. I graduated with my Master of Arts Management from Carnegie Mellon University in May 2020 and celebrated the occasion from my family home with a twenty-minute zoom ceremony. At the time, the only silver lining seemed like the mimosa in my hand and not needing to fight the crowds to see my family after walking across the stage. Everything else felt hollow and uncertain, especially as I faced a job market that seemed to have frozen over.

Flash forward to October 2022. For the first time since joining WolfBrown in January of 2021, I attended an in-person convening at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. What surprised and delighted me most were the moments “in-between.” Breaks weren’t used to turn over laundry or hurriedly dash outside with the dog. Breaks were used to connect and collaborate — to further probe ideas or share something else that couldn’t be exchanged in the larger session. Youth leaders were connecting with potential mentors from across the country. Organization leaders were collaborating with familiar and new colleagues. It was energizing to see and experience what the act of genuinely connecting could do — something we had possibly taken for granted until it was starkly and suddenly gone.

The experience breathed new life into my work. I may spend countless hours reading and writing behind a screen, but the moments spent in a dark theater or in intentional collaboration give my work something to stand on — give it meaning — and I’m forever thankful for them.

Collaborating Towards a Responsive Model

By Alan Kline

In 2020, “unprecedented” was voted the word of the year by Dictionary.com readers. Since then, it feels like the only precedent is how many unprecedented changes we have faced. Working on the Covid-19 Audience Outlook Monitor study, our team has watched this in real time. Audiences were slow to return, more selective, and less likely to subscribe. Many organizations have had to discuss if and how to transition to new programming, financial plans, and engagement models. The speed of these changes has been, well, unprecedented.

In conversations with arts administrators about transitions in the field, there is fear that the changes since the pandemic started are making our work harder without benefit. However, at least one change has inspired me: the very conversations we’re having. Organizations have been talking and sharing data as case studies for years, but now we’re seeing complete transparency, even when we don’t yet have answers and the data doesn’t look good. In our Covid study, hundreds of organizations shared full data sets and openly discussed challenges and their attempts to address them. This allowed a new level of shared applied research in real-time. Rather than watching a webinar with an expert sharing something that worked for them two years ago, we were discussing experiments in real-time. This meant that multiple organizations could iterate changes based on audience responses in quick succession.

The arts are facing many challenges right now, but we have many insights on how to address them. As we get more data on what works and what our audiences want, good ideas for solutions will only multiply. Working together in this responsive model, our ability to overcome and thrive could be unprecedented.

Transitioning From Treasure House to Tool Box

By Dr. Dennie Palmer Wolf

Once upon a time, I was an art student – the maker of giant landscape paintings where I had to stand on a step ladder if I wanted to paint the sky. But I was not great – or I lacked courage – it’s hard to say which. So I transitioned to thinking and writing and research, only occasionally touching on things visual – the way your hand palpates a burn blister – curious to see if it is still tender.

Then, this summer, we began work for Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and I fell back into that lush, tangled world of surfaces and all that lies behind and beneath. Moshe Safdie’s building hovers like a great dragonfly over a river in which you see the shadows of fish and turtles moving under huge colored glass spheres, tempting you to confuse above and below, moving and still, alive and not.

Through the months of those visits, I transitioned back to being alive through my eyes – botanical journals that must have been the everyday joy of the woman whom I imagined escaped from her kitchen, tromping the field and the bog drawing, drawing, drawing, the froth of a tulle ballgown, the stern beauty of a beaded Ojibwe bandolier bag, the demanding tumult of Mickalene Thomas’s painting.

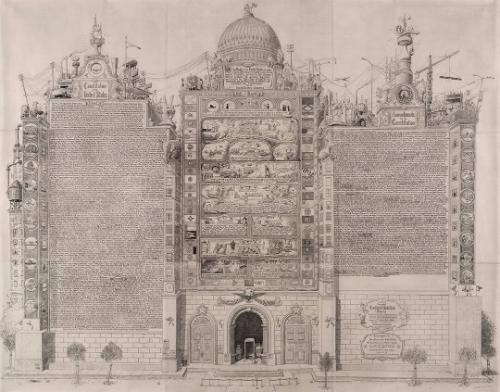

It was also a chance to behold (and to be held by) what a world made visual and alerting can mean to people’s lives. In the exhibition We the People: The Radical Notion of Democracy, there was more than an early copy of the Constitution. The timeline along the wall portrayed the roots of federation in the practices of indigenous peoples. In front of a printed copy of the 13th amendment, I heard a father murmuring to his infant daughter, “That’s where your history began.” Along the walls, Sandow Birk’s astounding line drawings portrayed the Constitution as some giant apartment-cum-temple housing a multitude of lives. An amazed teenager told her boyfriend – no permission asked – that she wasn’t at all done looking. It was hard to choose between watching the works and the lives those works were stretching and fulfilling.

All this watching and looking speaks to another transition: one deep in the lives of museums themselves. What if museums (and orchestras and theaters) beheld what was happening in that room? And what if they were as amazed as the young woman who would not leave the world Birk created? What if their verbs changed from ticketing, presenting, and exhibiting to inviting, convening, and questioning?

Of course, the lights have to stay on, the bills have to be paid, and workers deserve health insurance. But what if the point became discussion, even debate, as much as – or even more than a display? It would be a transition from archive to actor, or, as our colleague Marissa Reyes at Crystal Bridges put it, “from treasure house to tool box.”

Leaning into Community: Transitional Firsts in Arizona

By Surale Phillips

A serendipitous flight cancellation on November 4 landed me at Chandler Center for the Arts (CCA) to experience firsthand two transitional firsts for this Arizona arts presenter. Since leading several research projects for CCA, I’ve seen their team make many strides on their DEI journey but had yet to witness the results of our applied research. The center diversified its board, made bold programming shifts, and thoughtfully evolved its brand. All were informed by research and driven by bold leadership. But the event on November 4 was extra special. Not only did I get to attend the presenter’s first commissioned work — a sold-out performance of NORTH: The Musical, I also met Chandler’s first artist-in-residence, Michael Mwenso, who was also attending the show.

When I asked Terri Rettig, CCA Assistant Manager, how they realized this bold transition from presenting work to commissioning work and bringing in an artist-in-residence, she said, “We leaned into community.” After presenting Michael Mwenso (Harlem 100) in 2019, this musician, activist, and educator phoned the center to pitch the idea of a residency in Chandler. “We’ve never done that. And what artist picks up the phone and calls you? It doesn’t work that way,” Rettig reflected on the center’s initial reaction. Then, as Chandler folks tend to do, they said, “Yes, let’s make this happen” and found a way to make it happen. Michael Mwenso is now working directly as a musician, activist, and educator with local artists, students, and community members in a three-year residency. Michelle MacLennan, president of the Chandler Cultural Foundation and the center’s general manager, shares, “Michael wanted to engage with us because Chandler felt different. [That he reached out] was an acknowledgment of 20+ years of programming development for Black audiences, as stated in our strategic plan to expand and develop Black audiences since 2015.” MacLennan continues, “Artistic residencies were not an unknown to us, but we had not identified the right time/place or artists to fully jump in. Michael called at the right moment out of interest in our community and allowed us to engage directly with an artist, versus through an agency. This also fast-tracked the opportunities.”

In 2020, when the center presented Jazzy Ash’s (Ashli St. Armant) digital performance, they fell in love with her voice, immense talent, joy, and energy. St. Armant mentioned that she’d been looking for partners to get the work on stage. “We present work; we don’t commission work,” was the center’s initial response. Then, as Chandler folks tend to do, they said “Yes, let’s make this happen.”

“Just because we haven’t commissioned work, doesn’t mean we can’t,” thought MacLennan. St. Armant’s NORTH: The Musical was precisely the kind of work the center wanted to share with the community and the type of work the community had been asking for. MacLennan also shared that she felt the pandemic made room for the potential for these endeavors. “It allowed us to slow down a bit, reassess how we were impacting our local community, and take the time to think newly and broadly about our importance in the healing and response to our community’s needs.”

St. Armant created this piece to bring curiosity to conversations about slavery, to explore the complexity of being human, and to highlight the multi-generational story of grit, joy, and ingenuity of Blacks in America. It is a story deeply inspired by her own ancestors and many other real people who escaped plantations and dared to venture into the unknown through the network of the Underground Railroad. Three other performing arts centers across the country joined Chandler in co-commissioning this piece – Lied Center of Kansas (Lawrence, KS), Segerstrom Center for the Arts (Orange County, CA), and Playhouse Square (Cleveland, OH). As of this writing, NORTH: The Musical has already been picked up for national touring beyond these cities.

My heart sang along with the voices on stage, and my smile beamed watching kids and adults of all ages and colors rush to hug Mwenso in the lobby. This is what leaning into community means, taking bold firsts to make change happen. I’ve always referred to Chandler as having a “culture of yes,” and this is why.

Arts Versus Administration

By Kacie Willis

About ten years ago, after moving to Atlanta following graduate school, I had a conversation with one of my “theater moms” about how I wished I didn’t have to work a 9-5 in addition to pursuing my creative passions. “If I could just focus on my art 24/7, life would be perfect,” I thought. Still, I figured this aspiration was a long shot and found ways to maintain my creative focus while learning incredibly useful skills in various arts administration roles with organizations throughout metro Atlanta.

Cut to April 2020, when following the downturn in business in the fine arts and performing arts sectors, I unintentionally got a taste of what it feels like to support myself solely through creative work in digital media. When the outside world shut down, the virtual world exploded with possibilities for creators using video and audio. Through a series of bizarre events, I became a full-time podcast producer for my two shows, other brands, and independent content creators. This was the dream, right? As I sat in my room, day after day in lockdown, conducting remote guest interviews or editing episode cuts, I thought to myself, “Hmm, it’s weird how working on my creative projects 24/7 is starting to feel more like a chore and not an outlet for expression.” It was then that I realized the adage, “Be careful what you wish for,” can be pretty accurate sometimes.

We talk about balance a lot in the work world, often about work/life balance. Still, being an artist with a day job that I enjoy, one that helps me feel fulfilled and accomplished, is the type of balance that best suits my creative practice. As I transition back into the world of arts administration with WolfBrown, I am happy to be surrounded by colleagues who also have creative pursuits and interests of their own as we all work collectively to strengthen and inspire the sector through innovative research. I hope we will help support artists, administrators, and every creative spirit in between.

In Memory of Geoff Nuttall

By Dr. Thomas Wolf

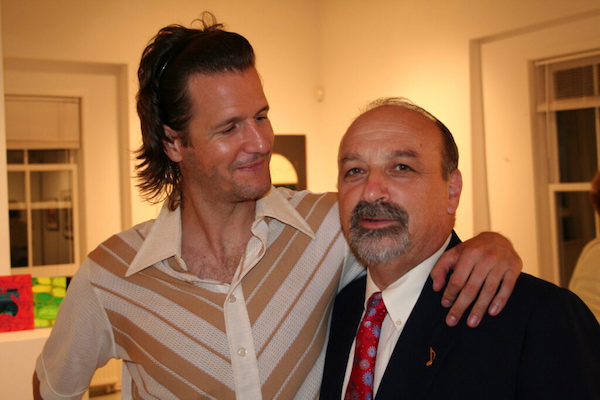

Holiday time is generally a happy time for me and my family. But this holiday I am thinking about a tremendous loss to the music world in general and to me personally. Geoff Nuttall, the remarkable violinist and founding first violinist of the Saint Lawrence String Quartet died on October 19th of pancreatic cancer at the age of 56. Geoff was one of those who brought the chamber music experience into the 21st century for so many people. In addition to being a superb instrumentalist, The New York Times dubbed him the “Jon Stewart of chamber music,” adding that he “established a new style of presentation that juxtaposes the ridiculous with the sublime, [delved] into serious musicology and casually [used] technology. In short, he [was] subtly redefining what a chamber music concert can be.”

Among many other things, Geoff ran the chamber music program at the Spoleto Festival and so popular was he as a performer and host that it was never easy to secure a ticket. I worked with him for many seasons at Bay Chamber Concerts in Maine where the Saint Lawrence was the resident quartet and I was the Artistic Director. Whether planning programs with him, thinking about introducing new commissions, observing him coach youngsters, or watching him be the life of any party, Geoff’s energy was boundless. For those of us who had the experience of performing with him, he inspired us always to play better. We are all impoverished by his death.