As my research into the immersive paradigm goes deeper and deeper, I’m continually reminded that we are three-dimensional human beings. We do not inhabit a flat, two-dimensional world; instead, we live in a three-dimensional environment, experiencing life through movement and interaction with our surroundings. Our senses have evolved to allow us to engage with the world, developing a sense of balance, depth, smell, touch, and more—a complex array of perceptions that help us understand our position and the world around us. We make choices and possess free will, the primary driver of our “sense of presence” in the here and now. We communicate and receive external input constantly. However, many of the narratives we experience, particularly the majority of mass media we unconsciously rely on, are two-dimensional or have adapted to two-dimensionality, which does not reflect how we interact with the world as human beings.

In a previous newsletter, we referred to the “Experience Economy” (Pine and Gilmore) – the idea that consumers today prefer to pay for unique live experiences rather than goods or services. This yearning individuals have to actively participate in the stories that interest them and to have experiences where they are active creators rather than passive consumers is reflected in the growth of immersive entertainment attractions, such as theme parks, immersive theater, immersive art exhibitions, and virtual reality.

If arts presenters and producers are to move with this inexorable evolution, the time has come to develop new narrative models that are more natural, more organic, and less limiting for us as an animal species. New immersive narrative models have the power to activate sensations we are unaccustomed to experiencing in conventional arts presentations.

Take, for instance, the direct stimulation of memories through interaction. The project “In Pursuit of Repetitive Beats” is an immersive virtual experience that transports us directly to the late 1990s as we search for an acid-house rave in the English suburbs. The sheer number of era-specific details we can interact with firsthand through an Oculus headset and the choices we make during the simulation allow us to relive those particular sensations. Immersive design makes that historical period accessible, encouraging participants to interact and interpret, drawing from their own experience.

In immersive design, the story is shaped, in part, by the participant, as they will ultimately be the ones who’ll choose their own path through the story as a co-creator. This position must be authorized, in some way, by the designer, who is no longer the sole author but also a facilitator, granting the user some degree of agency over their experience.

Agency leads to exploration, and exploration, in turn, leads to discovery. Director and artist Tim Burton masterfully interpreted the relationship between agency, exploration, and discovery in his latest immersive experience, “Labyrinth.” This vast exhibition space transports visitors through various film worlds, including Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, Mars Attacks, Wednesday, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The diverse rooms are filled with original artwork, sculptures, and specially created animations.

As the name suggests, the exhibit’s layout is a labyrinth. Visitors independently choose their path among more than 300 possible routes, allowing myriad ways of interacting with the work and, most importantly, enjoying the atmosphere. Upon entering the experience, the journey’s progression is up to you, making the encounter unique and unrepeatable.

What immersive experiences strive to accomplish is to effectively eliminate all unnatural operational limitations and present an environment in which people can interact with one another and the work itself. In essence, they seek to break down the “fourth wall.” Breaking down this wall not only calls for dynamic storytelling that continuously evolves during the experience; it also necessitates rethinking the design and layout of the exhibition spaces.

A prime example is the immersive musical by David Byrne and Fatboy Slim, “Here Lies Love,” which centers around Imelda Marcos (the former wife of the Philippine Prime Minister). In this production, the famous Broadway Theatre—a traditional proscenium theater built in 1924—is transformed, in part, into a massive nightclub. The performance space for the actors is set amidst a standing, dancing crowd on the floor where the front seating section would typically be.

Immersive design seeks to ensure that people are more than just passive consumers. It doesn’t involve the audience merely sitting in a chair and being told a story, which would be akin to approaching a painting or a sculpture on a pedestal — an experience that more and more people find esoteric and puzzling.

True fans don’t just want to watch another… and another… and another episode; they want to dive into the action and make a direct connection. They want to inhabit the story’s world.

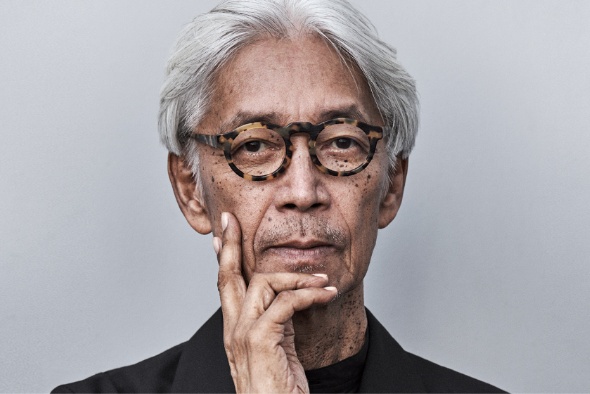

Consider the case of master composer and artist Ryuichi Sakamoto, pioneering electronic musician and Oscar winner for the “Last Emperor” score. Before his passing, Sakamoto left behind an immersive exhibition as his final work. He was in the planning stages of “KAGAMI,” scheduled to premiere this summer at The Shed in New York City. According to representatives of the mixed-reality content production studio Tin Drum, the program represents a new kind of concert, fusing moving photography with the real world in a mixed-media presentation. Though Sakamoto will not be physically present, audiences wearing optically transparent devices (e.g., smart glasses) can view a virtual Sakamoto performing on piano alongside dimensional art aligned with the music. It seems as though Sakamoto has, in a way, survived—not just through his music but also through this deeply immersive experience.

We are only just beginning to truly explore the power of immersive storytelling. Reconfiguring the relationships between story, space, and time will allow us to activate greater public interest in art, artists, history, science, and contemporary issues and ideas in new ways. It will also require us to think very differently about programming.