This piece is dedicated to the memory and work of Don Glass, an artist, educator, and researcher who devoted his considerable imagination to thinking about the many ways in which it is possible to invite people in.

By Dr. Dennie Palmer Wolf

At age 9, Ron Mace contracted polio. From then on, he took on barriers. He took on flights of stairs to reach his classes and bathroom doors too narrow for a wheelchair. He took on no easy way to utilize what was supposed to be “public” transit. Undaunted, he went to architecture school with the intention of dismantling those barriers. Mace was an outspoken champion of North Carolina’s 1973 adoption of Chapter 11X. That was the first accessibility-focused building code in the United States and foundation for the later movement to pass federal legislation prohibiting disability discrimination. This legislation included the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

In 1989, Mace founded the Center for Accessible Housing, which later evolved into the Center for Universal Design, a leading resource for research and information on accessible design in housing, products, and the built environment. He, along with his wife Lockhart Follin-Mace, who also was a wheelchair user working in public policy, re-defined the concept of design. For them, design was not how something looks, or even how well it works, but how it affects the lives of people who use it, live in it, or engage because of it.

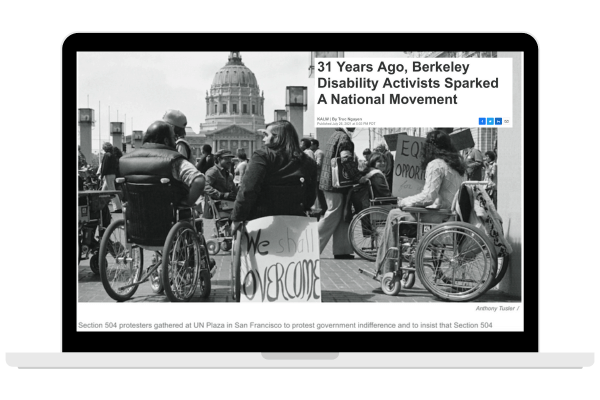

Americans with Disabilities Act

Their work, together with that of countless other activists, inspired the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which became law in 1990. It builds on the scope of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to prevent discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public.

The ADA ensures that people with disabilities have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else.

For an amazing timeline of the evolution of disability rights, see here.

In the Maces’ Footsteps

Traditionally, the arts – long thought of as refined, perfect, and flawless – have been off-limits to individuals with disabilities. Still, there are others who followed in the Maces’ footsteps to insist upon accessibility in the arts and beyond. For example, in 1983, artist and psychologists Florence and Elias Katz founded Creativity Explored. This is an arts studio that served adults with disabilities in San Francisco. Guided by the belief in art as a two-way street, the Katz’s studio provided access to expressive opportunities for people who were usually closed out of making and creating. The studio also served as a gallery space where the remarkable work by those individuals could challenge public perceptions of what – and how – adults with developmental disabilities can contribute to the arts.

In re-thinking opportunity structures for participants, the Katz’s and the remarkable artist-staff who have kept the work alive have guaranteed that these adults have access to instruction, fine arts materials, sustained memberships (some for up to 30 years), exhibitions, sales, and income from the licensing of their designs to outlets like CB2. To this day, the organization’s website features portraits of its board members and advisors drawn by workshop participants.

In a similar spirit, the work of Access/VSA at the Kennedy Center has sought out and acknowledged the work of artists and performers with disabilities. More recently, a consortium of arts and arts education organizations in New York has begun training teaching artists. They are using the GIVE guide, a free online resource: Guide to Teaching Artistry in Inclusive Settings. It was developed by teaching artists for teaching artists. The guide addresses inclusive curriculum, inclusive language, and classroom and behavior management for inclusive settings. (This work will be a major feature in this summer’s Amplifying Creative Opportunities Issue 3.)

The Universal Design in Arts and Culture

Exercising their capacity for imagining possibilities, artists and arts organizations have built on and expanded this idea of universal design, both literally and conceptually.

PHAMALy

In 1989, PHAMALy (Physically Handicapped Amateur Musical Actors League) was founded by five students living with disabilities. They had grown frustrated with the lack of theatrical opportunities. These founders were ahead of their time in building an inclusive organization. The organization directly served disenfranchised individuals with disabilities from all racial, ethnic, gender, and class identities.

The Phamaly Theatre Company (PTC) gives actors a supportive space to explore and develop their craft. It also empowers artists within their disability identity. Furthermore, it educates the community about access and inclusion. Additionally, it entertains audiences with high-quality, award-winning theater. This theater re-invents musicals and classical theater works, ranging from Guys and Dolls to Midsummer Night’s Dream. This work is documented in imperfect, a recent film made by and with the members of PTC. In the same vein, performers like Yvonne Rainer and Jerron Herman and companies like Axis Dance have re-imagined movement. They treat their embodied differences as artistic resources. They highlight what is unique and beautiful about their bodies in motion, and expanding the definition of “moving” – in every sense of the word.

Human Library Organization

The Human Library Organization re-imagines pages as people. Begun in Copenhagen in the spring of 2000 as a project for Roskilde Festival, the core idea was to “publish” individuals as “open books” who would meet with a small group of “readers” in a safe “library” environment to speak about and answer questions about their lives. “Books” included people who are often stigmatized such as deaf individuals, people on the autism spectrum, transgender individuals, people living homeless, extremely tattooed and pierced people, and others.

This inclusive library of “books” provides “readers” with opportunity to “check out” individuals who will challenge their stereotypes. It offers people volunteering to be “books” with the opportunity to share their full humanity. In this way, the Library, like a fully accessible theater or audition space, builds an environment that challenges stereotypes and prejudices. It is a place where real people are on loan to readers and where difficult questions are expected, appreciated, and answered. Their tag line is “Unjudge someone.”

Arts and Homelessness Festival

Finally, consider the city of Coventry. It was selected as the UK City of Culture in 2021. It made the bold choice to design its program with its citizens, including individuals experiencing poverty and homelessness. The resulting festival amplified the voices of people with lived experiences of homelessness in the Arts and Homelessness Festival, a week-long event co-designed and staffed by people with lived experiences of homelessness. The festival included theater, a photographic portrait exhibition, a sleep-out, and the second ever International Arts and Homelessness Summit, designed to ensure that the limelight of 2021 could be converted to immediate and consequential change. (Read more about this in Amplifying Creative Opportunities Issue 3, when we profile the impact of working on this festival on young researchers and evaluators.)

At its most direct, universal design taught us to normalize need: ramps, lower bathroom sinks, and close captions are human needs, not the outsized demands of needy people. They are like prescription glasses or hearing aids – extensions of human capacities we all have a right to.

Stepping Back: Three Lessons of Universal Design

Universal design has many legacies for thinking about building opportunities.

- Universal design benefits all of us, expanding experience for everyone involved. Consider a recent concert by Sisterfire at the Kennedy Center. It was signed by an amazing performer who conveyed not only the lyrics, but also the contours and the expressivity of the musicians’ wordless vocal improvisations. His choices enlarged the concert for everyone in the audience.

- Universal designs model how to notice, take on, and replace deeply-embedded, widely-held exclusionary ways of thinking and acting. The concept of neuro-diversity dissolves the ingrained duality of normal v. abnormal. In so doing, it alerts us to the world experienced in multiple ways. The idea of a continuum of gender identities dislodges the immutable binary of sex as assigned at birth. Both are ramps to thinking about human variety and relatedness, rather than separating who we are into disjunct categories.

- The work of universal designers teaches us about the long arc of equity work. Ron and Lockhart Follin-Mace began their work in the 1970s. However, the film imperfect played in festivals in the 2020’s. That is half a century of determined, hopeful work on inventing opportunity structures. And there is more coming–sourced by their original determination.

This post is a part of the Taking the Long View focus of our Amplifying Creative Opportunities newsletter.

Read more of the second issue of our Amplifying Creative Opportunities newsletter.

Read another Taking the Long View piece “Five Steps for Equity” by Dr. Thomas Wolf.