The daily practices and tools we use in both designing and evaluating programs are some of the most powerful, but least acknowledged, ways in which we enshrine – or examine – our ways of doing business. In the following piece, Kathleen Hill reviews her use of “ant trails,” one of the most common observational tools in museum studies. She explores what they make visible and the assumptions that underlie them.

– Dr. Dennie Palmer Wolf

Part of the joy of working in the Creative Opportunities practice area at WolfBrown is having the chance to apply rigorous research methodologies in less ventured settings.

Consider tracking and timing visitors in museums. Institutions around the world have used the evaluation methodology since the early 20th century. In recent decades, several have advanced the practice with the help of technology. For example, as early as 2014, the Guggenheim installed beacons. These beacons track how quickly visitors move through a museum and what works were most popular. It also developed a push notification system that would send guests information about the pieces they were closest to. Other museums like the Indianapolis Museum of Art, The Deutsches Museum in Munich, and the Hatfield Marine Science Center Visitor Center in Newport, Oregon are experimenting. They want to track visitors’ eye movements as they engage with pieces. Some have taken these methodologies further to gamify or augment the visitor’s experience with augmented reality or visitor technologies.

In March and April of 2022, we collaborated with the Children’s Museum of Manhattan to implement a manual tracking and timing evaluation. We looked at visitor behavior in the Superpowered Metropolis: Early Learning City exhibit.

About the Exhibit

The exhibit is a hands-on, interactive, and colorfully immersive exhibition. Children ages 0-6” are encouraged to be the heroes alongside super-powered pigeons Zip, Zap, and Zoom! In this comic-book-inspired NYC world, Zip, Zap, and Zoom serve as guides. They unlock children’s executive functions through everyday moments and activities:

- Zip, Self-Control Champion – A calm coach who encourages “power pauses” before acting. Zip encourages thinking things through, resisting distractions, following directions, and taking turns.

- Zap, Working Memory Master – A witty thinker who juggles information in mind. Zap is always at the ready, remembering instructions, and skillfully organizing and sorting information.

- Zoom, Mental Flexibility Guru – A curious inventor who sees things from multiple perspectives. Zoom switches gears easily and solves problems creatively.

Methods Overview

The exhibit had been closed throughout the COVID-19 lockdowns. However, our work in March and April of 2022 was a great chance to gauge how early visitors to the exhibit engaged with the various activities throughout the space. Then, we explored how this engagement may have strengthened adults’ knowledge of the three executive functions. These functions are self-control, working memory, and mental flexibility.

On several Fridays and Saturdays, I trained and worked with two early childhood educators from the museum to manually track families as they moved through the exhibit. We also surveyed several parents/guardians before and after they went through the exhibit. We wanted to determine if time in the exhibit affected their knowledge of executive functions.

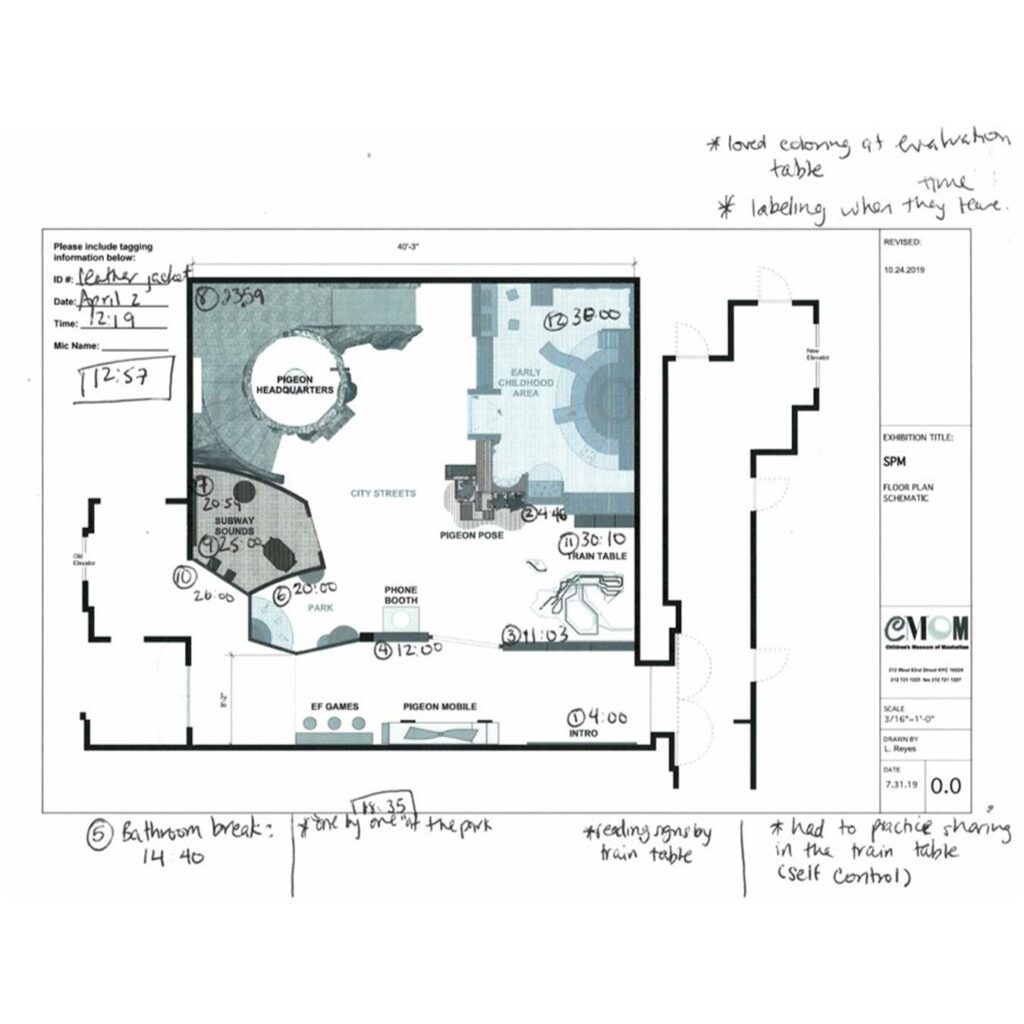

Ant Trailing

We borrowed from a method that is commonly referred to as “ant trailing.” Below is an example of one of the maps that one of the educators completed on Saturday, April 2nd. We did not draw lines from stop to stop as one might in traditional ant trailing. Instead, each of the stops are labeled in chronological order as well as with a timestamp that is aligned with a timer. There are also several notes along the margins of the page that indicate particular habits or behaviors that may impact the flow of the map or call out a particular interaction with the exhibit. Of course, no detail was too small. We tried to capture everything from bathroom breaks to engagement with the evaluation table that featured coloring activities and our incentives/compensation for participation. For example, we provided children’s books, free passes to the museum, and tie-dye kits.

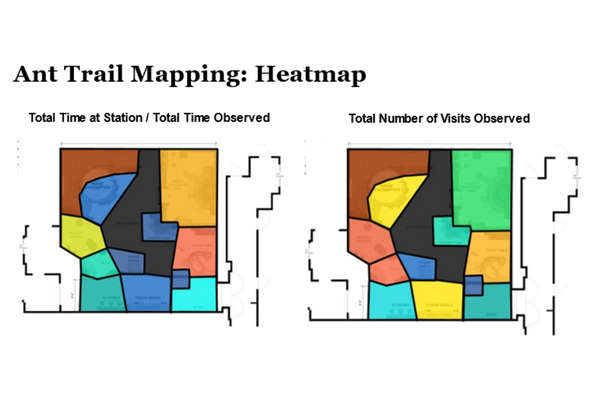

Overall, we were able to collect 8 hours and 17 minutes (08:17:00) of observed visitor interactions with the exhibit across 25 visitor groups. The results were aggregated across the visitor groups to create heatmaps of Total Visits and Total Time Spent. Warmer tones indicate where a larger portion of visitor time was spent/visits occurred. Cooler tones indicate where a smaller portion of visitor time was spent/visits occurred.

The work looking at visitor behavior revealed exciting discoveries and opportunities. These were not only about the exhibit and the potential for its future iterations, but also the use of tracking and timing evaluation techniques in children’s museums.

Discoveries

Time Spent v. Number of Visits:

- Time spent and number of visits were not always synonymous. In other words, some portions of the exhibit encouraged frequent, but brief visits whereas others encouraged fewer, but sustained visits. For example, there was a space dedicated to infants in the top right corner of the exhibit. While few groups ventured back there, those that did spent a sustained amount of time there because it was age appropriate for their children (e.g., safe for crawling in a contained space, developmentally appropriate toys and activities, “no shoes” zone, etc.). The important thing is to strike a balance between the two measurements so that learners of all levels and styles can find something to excite them during their visit.

Involvement of Museum Staff:

- Working alongside the museum educators was an absolute delight for me as I had the chance to gain inside knowledge about the day to day of the museum and the ways in which the exhibits operate. It also proved to be exciting for a few of the regular families as their children recognized them from other classes or events. Above all else, I know that it helped to establish trust and buy-in in the evaluation as well as strengthened the capacities of the educators in evaluation and research which they could apply to other research efforts in the museum.

Challenges and Opportunities in Studying Visitor Behavior

Children’s Engagement

- Children appeared highly engaged by the exhibit. Certainly, they moved around the exhibit quickly, spending time in many different areas and at many different stations. Additionally, families stayed in the exhibit for a fairly long time. They stayed over 20 minutes, on average, which is a long time for a 3-year-old! However, as an evaluator, this proved to be quite the challenge to track! Rather than the steady pace of an adult visitor in an art museum, the toddlers were almost like pinballs. This may have impacted the adults’ ability to fully engage with the signage in the exhibit.

Children as Study Subjects:

- As mentioned above, children don’t move through an exhibit in the same way that an adult visitor would. This is especially true when there are so many exciting nooks of an exhibit to explore! More often than not, it’s also difficult to encourage them to reflect back on their experience as to why they went were they went — why they stayed, where they stayed. To study children’s habits in museum spaces, patience, flexibility and creativity are essential. This is what led to several of the adjustments that we made throughout the evaluation process. For instance, we introduced activities at the evaluation table and removed the literal trails from the mapping process.

Adults’ Engagement:

- Adults reported that they appreciated the exhibit and know that their children had a fantastic time. However, they often shared that they had a hard time reading the information on the walls which featured blurbs from Zip, Zap, and Zoom. The blurbs discussed how to encourage super-powered learning through play outside of the museum. For future iterations of this exhibit and others like it, the helpful knowledge needs to come off of the walls. Instead, it should step into the exhibit to encourage super-powered play and learning for all! Whether it be through educators guiding visitor groups through the activities or more interactive technologies (e.g., mirror screens, augmented reality, etc.), the enhanced engagement strategies will help all visitors make the most of their visits.

Next Steps for the Museum in Studying Visitor Behavior

The complete results of the tracking and timing process as well as the exhibit pre-post survey were shared with museum staff in November of 2022. They are already using these results to inform operations in the current exhibit. Results also support and inform future exhibitions in the Children’s Museum of Manhattan’s new home!

Next Steps for Amplifying Creative Opportunities

In taking on tracking and timing work for the Children’s Museum of Manhattan, several questions about the evaluation tool emerged. These did not emerge as a critique of the museum. Instead, they came as a way to understand the assumptions underlying this widely-used methodology. How might it evolve in a way that could help institutions think about the experiences of wider groups of visitors?

Visitor Groups

The ideal structure for our study looking at visitor behavior would be one child and one parent. However, that was rarely the type of group that we saw moving through the exhibit. In fact, we often saw family or child care groups. Most often, an adult responsible for multiple children would decline participating in the evaluation. They had to keep their eyes on the children as opposed to a survey page. Instead, an adult pair with one-two children would often consent because one adult could engage with the evaluator. The other could supervise play and engagement in the exhibit. Fortunately, we were able to adjust mid-way through the observation process to introduce activities at our evaluation table (e.g., coloring pages). This helped in capturing some children’s interest just long enough for an adult to hear about the evaluation, but not all.

This led me to wonder: by the very nature of our research design and tools, whose perspectives and opinions do we miss when studying visitor behavior? How can tracking and timing be improved to capture the dynamics of family or peer learning and engagement?

This led me to wonder: by the very nature of our research design and tools, whose perspectives and opinions do we miss? How can tracking and timing be improved to capture the dynamics of family or peer learning and engagement?

– Kathleen Hill

Mapping & Equity in Studying Visitor Behavior

When using tracking and timing, we might not get the chance to learn about the very conditions that allow for coming, going, and staying in a space.

- For example, is someone hurriedly rushing out because they are disinterested? Or is it because they have to catch a bus in 10 minutes or risk waiting over an hour for the next one that will get them home?

- Are children hesitant to engage in the exhibit activities because they are shy? Or is it because they’ve never been to a museum before and they aren’t sure where to start?

- Are other children playing freely because they come here every Friday? Are the exhibits as familiar as the hallways in their apartment building?

Fortunately, we tried to mitigate against some of this by asking visitor groups. We did this by asking if they were local to New York City. We also asked if they were repeat visitors or members. However, we had not asked about museum attendance in general.

Opportunities and Questions Unanswered

The opportunity to track and time multiple visitors will hopefully help to find the “average” experience. However, does the average help institutions deliver on their promises to be more equitable, inclusive, and accessible? How can we, as evaluators, help institutions consider the stories in the 10th and 90th percentiles, as well as the average?

The Children’s Museum of Manhattan rigorously evaluates the effectiveness of their community outreach and engagement programs. WolfBrown occasionally supports them in this work. This particular evaluation was a chance for the museum to understand the interactions of as many families and groups as possible. Still, what would it have looked like to add an additional layer of analysis? Could we truly understand and serve all families and groups who visit? If we get the chance, it would be exciting to add this dimension to the work. Then, we could honor the museum’s outreach commitment.

Hopefully, future tracking and timing opportunities can help to answer some of these questions about visitor behavior. If there are any out there, please send resources our way!

This post is a part of the Re-Tooling the Trade focus of our Amplifying Creative Opportunities newsletter.

Read more of the first issue of our Amplifying Creative Opportunities newsletter.