This piece is part of a larger series examining more equitable practices in arts research and consulting. Our goal is to reflect openly and self-critically on the underlying processes, assumptions, and structures driving inequity and what would make the arts and culture sector more equitable.

One question of equity that may be overlooked in arts research is who formulates the questions that research will address. In most applied research (i.e., research that occurs in the field, outside of the laboratory), the relationship between investigator and practitioner is asymmetrical: the investigator formulates questions based on theory and prior research; the practitioner’s role is merely to provide the setting in which those questions will be addressed.

In research conducted for the purposes of program evaluation, the relationship between investigator and practitioner is typically more equitable: the practitioner has questions about their program that the investigator will help them address. These questions range widely and include:

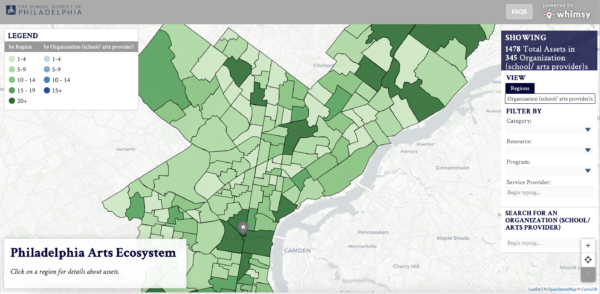

- How are opportunities for arts education distributed geographically within a school district?

- What are the impacts of different levels of engagement with live theater on children’s social awareness?

Thus – and unlike in many examples of other forms of applied research – investigators conducting program evaluations approach practitioners asking, “What do you want to know more about?” rather than “How can your program serve as a context in which to address my pre-formulated questions?”

This more equitable arrangement is a hallmark of a researcher-practitioner partnership (RPP), a particular form of research collaboration that has gained interest in recent years. Examples of RPPs can be found in many fields, from education to juvenile justice to public health. In addition to the more equitable role of practitioners and researchers in formulating the questions to be addressed, one of the key characteristics of RPPs is their duration. Typically, researchers will work with a practitioner organization long enough to collect their data, at which point the collaboration ends. In RPPs, data collection may continue for years as the questions of mutual interest to the practitioners and researchers evolve over time.

In the remainder of this post, we present an overview of WolfBrown’s RPP with the New Jersey Symphony that endured for over a decade.

Results from a Researcher-Practitioner Partnership in Arts Education

Like many symphony orchestras, the New Jersey Symphony, located in Newark, New Jersey, operates a youth orchestra for children and adolescents. Since its founding in 1990, the youth orchestra has served nearly 2,600 youth, and over its history, the membership of the program has change. Although the youth orchestra’s founding mission was – and continues to be – to serve qualified middle- and high-school students (and especially Black and Latino/a youth in the Greater Newark area) by the early 2010s the young musicians participating in the orchestra had begun to be disproportionately White and from relatively affluent families. After recognizing this fact, the Symphony reorganized its youth ensembles and expanded its recruitment strategies, setting a target membership of a minimum of 45% Black and Latino musicians that it has met or exceeded nearly every year since 2015. However, the demographic composition of the Symphony’s youth orchestra in the early 2010s was in no way unique: as explained in detail elsewhere, children from historically marginalized communities (who are also disproportionately likely Black and/or Hispanic) continue to face multiple barriers to participation in these ensembles, including limited access to private lessons and high-quality instruments.

In response to these realities, in the 2010s, many orchestras began to operate ensembles inspired by the El Sistema program, which José Antonio Abreu founded as a means to expand access to music education in Venezuela. Although the merits of El Sistema programs for participants have been fiercely debated, there is little doubt that these programs expanded access to participation in youth orchestras among socioeconomically and racially-diverse children. For example, in a study of 12 El Sistema programs from across the United States, nearly three-quarters of participating students identified as a member of a racially or ethnically minoritized group.

One of the programs included in this study was the New Jersey Symphony’s Character, Achievement, and Music Project (CHAMPS). In 2012, the Symphony retained WolfBrown to assess the program’s impacts on participating students. Thus began a researcher-practitioner partnership between the staff and leadership of CHAMPS and WolfBrown. In retrospect, that partnership can be divided into three phases, delineated by the changing goals of the program and the orchestra.

Phase 1 (2012 – 2014): The Extra-Musical Benefits of Music Education

As its name would imply, the Character, Achievement, and Music Project (CHAMPS) focused primarily on participants’ development in areas beyond music, particularly students’ academic achievement, and the factors that might drive that achievement (e.g., perseverance, classroom behavior). As such, the questions in which Symphony staff and leadership were most interested revolved around whether students were making gains in these areas, and those researchers (led by your author) were only too happy to oblige. The 2010s saw a proliferation of studies examining the extra-musical benefits of music education for children’s development, particularly for children whose development may have been adversely impacted by poverty and associated risk factors. WolfBrown’s evaluations of CHAMPS in these early years suggested that participation in the program was associated with higher levels of academic achievement and driving factors. However, for practical and ethical reasons, employing an experimental design that could establish whether participation caused these changes was not possible.

Phase II (2015 – 2019): Individual Musical Achievement

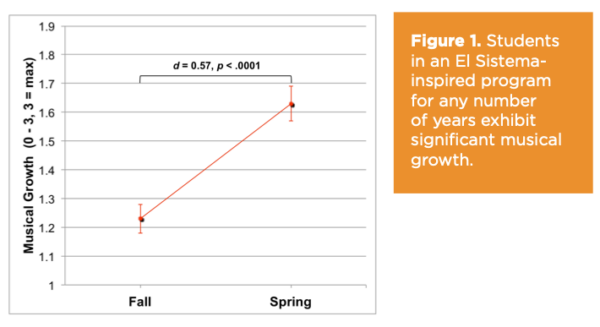

Beginning with the 2015-16 season, students’ musical growth became a focal point for the evaluation of CHAMPS. This was due, in part, to the participation of the Symphony in the aforementioned study of Sistema-inspired programs and that study’s underlying theory of change, which asserted that any extra-musical benefits of students’ involvement in a music education program were conveyed by what students learned about and through music. This study produced evidence that students enrolled in CHAMPS and its sister programs throughout the United States experienced substantial and statistically-significant growth as young musicians.

These effects could be causally attributed to the education students received in these programs, given the implausibility of the counterfactual (that students would have become better musicians absent the program’s influence).

Phase III (2020 – 2023): Ensemble Behaviors & the Renaissance of Orchestral Music

In late February 2020, just before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus pandemic, WolfBrown researchers met with the Symphony staff and leadership to discuss plans for the upcoming season. At the meeting, the successes of CHAMPS were discussed, manifest in nearly a decade’s worth of findings demonstrating the program’s positive impacts on diverse students’ musical and extra-musical development.

However, the discussion focused on the need for the Symphony to re-envision its training programs, given two emerging realizations:

- One of the sobering findings from the evaluations of CHAMPS and the national study of Sistema-inspired programs was that, despite the clear evidence of students’ musical growth, few students enrolled in those programs were able to gain entry via audition to the upper-level youth ensembles run by those programs’ host organizations. In many cases, this resulted in a two-tiered structure, with an upper-level ensemble of affluent and predominantly White students and a Sistema-inspired group comprised of students from less-affluent families and REM backgrounds.

- Another question raised by CHAMPS evaluations, the national study, and the emphasis in the field more broadly on the extra-musical benefits of music education was whether this emphasis was creating inequitable expectations for music education as a function of students’ backgrounds. For the affluent (and disproportionately White) students participating in upper-level youth orchestras, the expectation was musical excellence; for the students from lower-income families (who were also disproportionately from minoritized backgrounds) in Sistema-inspired programs, there were strong expectations for extra-musical benefits.

The Symphony determined to take a decidedly different approach to their reimagined Training Ensemble. They would be led by professional conductors, with lessons offered by members of the Symphony. The expectation for students would be growth, not only in their musicianship but also as members of an ensemble in which every musical role – from the concertmistress to the third trombone – was regarded as equally important. The program’s ultimate goal was to serve as a model for how a youth orchestra could serve to engage the diverse students and their families in orchestral music and, thereby, the diverse residents of the cities in which nearly every major American orchestra is located.

Coda

Although a virtual version of this program was offered during the pandemic, it was not until midway through the 2021-22 season that the in-person version could be implemented, and not until the 2022-23 season that it could be implemented in full. The evaluation of this first full year of the program yielded findings of not only musical growth among participating students but also growth in students’ sense of what was possible for them as young musicians, the specific areas in which they’d developed and where they had yet to improve, and of their sense belonging as members of a musical ensemble.

Unfortunately, as of this writing, the partnership between the Symphony and WolfBrown has come to an end due to lack of financial support, though the Symphony’s Training Ensemble and the youth orchestra program as a whole will continue. This illustrates the difficulties of sustaining music education for diverse students without adequate public support and the dangers of forcing organizations to rely on private funders to sustain their programs for children. But it also illustrates the challenges of maintaining long-term RPPs, particularly in arts and arts education, given that neither RPPs nor the arts have historically been priority areas for research funding. Indeed, the largest funders of research in the United States – the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation – tend not only to be disinterested in research in the arts (notwithstanding some notable exceptions) but quite deliberately constrain their investments to focus on theory-driven research that addresses questions posed by investigators (that is, not RPPs).

That said, there is some reason for optimism. WolfBrown is currently engaged in an RPP with Arts for Learning Maryland to evaluate their Start with the Art Program, which delivers arts-integrated English Language Arts and math lessons to students in Prince George’s County (Maryland) schools. This partnership is supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Education and Innovation Research (EIR) grant program, designed to foster long-term collaborations (five or more years) between practitioners and researchers.

This is piece is part of our series on equity in the arts. You can read other posts here:

Arts Outcomes Worthy of Pursuit – Joanna Borowski and Samuel McDonald of the New Jersey Symphony’s Education and Community Engagement Department share outcomes they considered worthy of research for their Training Ensemble.

Access to Evaluation Services – Finally, our colleague and collaborator Allison Russo shares how close to 100 arts education organizations in Newark are working together to gain access to quality evaluation services.