As the year draws to a close, we take time to reflect on what has shaped our work at WolfBrown, both the milestones we’ve reached and the shifts in perspective we’ve experienced. Some of us look back fondly at what we’ve accomplished this year, at transitions in our personal lives, and others take a broad view of trends in the arts. Together, our reflections stretch from decades past to the possibilities of 2026 and beyond.

Contributions

- Can We Reimagine Our Futures? — Alan Brown asks whether the arts sector can move beyond survival mode to collectively design bold, sustainable futures.

- The AI Revolution — John Carnwath looks at the nature of transitions in careers, life, and the world, and questions whether we need these markers to measure progress.

- 2026: The Year of the Connector — Erin Gold considers a year of data that points to one clear opportunity: helping people connect through the arts.

- Hope for the Future — Steven Holochwost reflects on eighteen years of change at home and at work.

- Multiplying Bills — Dennie Palmer Wolf writes a tribute to Bill Keens and to the countless creatives whose lives multiply meaning for others.

- How One Granny Square Changed Everything — Surale Phillips shares how the shift from program-centric to purpose-driven marketing fosters deeper audience connections.

- Two Becomes One — Claire Pavlik Purgus remembers a vibrant cross-cultural wedding in India and the transition that binds two families into one.

- Horses, Buggies, and the Future of Arts Consulting — Thomas Wolf describes forty years of change and continuity in arts consulting.

Can We Reimagine Our Futures?

By Alan Brown, Managing Principal

So many of us are being called to manage previously unthinkable transitions. While many artists and cultural organizations are thriving, many are not. The post-pandemic “recovery” has been uneven and has left us facing profound challenges:

- An eviscerated federal support structure for arts and culture that needs to be reimagined

- A sector still figuring out how to nurture and support artists and other creatives, at scale

- Weak arts education/creative learning ecosystems in many areas, and persistent inequities of opportunity

- Permanently altered organizational cost structures, further shifting reliance on fundraising

- Boards reckoning with structural deficits year-over-year, having depleted cash reserves, and still no roadmap to sustainability

- An unwillingness or inability to reshape public programming for a more diverse public

- A philanthropic sector tapped out by making operating grants and therefore unable to address longer-term capitalization needs that would lead to broader structural change

- A legacy of nonprofit infrastructure that, by and large, does not address the cultural interests of the majority of the populace

- A well-financed commercial entertainment sector, increasingly savvy about providing the kinds of experiences that the public wants

In this environment, the Overton Window should be wide open to new policies and structures. All too often, however, a survivalist mindset shuts down creative thinking about alternative futures.

Are we powerless to design brighter futures for our creative practices, our creative businesses, our nonprofit organizations, and our local, regional, and national support structures? No, I don’t think so. But doing so will require us to think beyond what we know and pool our resources in new ways that allow us to take risks we’ve not been able or willing to take.

Over the coming years, we can—and must—boldly reimagine our futures. As my WolfBrown colleagues point out, there are many bright spots. Every board member, every nonprofit administrator, every artist, every arts educator, every foundation funder, and every individual philanthropist has a role to play in this transformation.

As 2025 draws to a close, it seems we are at an existential fork in the road as a sector. Can we reclaim the idea of “transformational change” as something intrinsically positive—the product of our collective imaginations—rather than something bad that happens to us against our will only when bankruptcy knocks at the door?

I wish you all the grace and fortitude required to face down the extraordinary challenges ahead of us, and turn them into the vision, capital, and bold strategies for public engagement that will propel us towards a more democratic and a more sustainable sector.

The AI Revolution

by John Carnwath, Principal

In reflecting on transitions in 2025, one would be remiss not to mention Artificial Intelligence. Regardless of where one stands on the many heated debates circulating around the use of AI—appropriation of creative works, intellectual property, and personal likenesses for training purposes; mind-blowing investment in largely unproven technologies; deepfake videos; surveillance; and more—it’s difficult to escape the sense that something very big is on the horizon.

AI’s impact on my personal and professional life has been limited so far. My brother, a musician, has been using AI extensively to promote his latest album, and on a whim asked ChatGPT to create a visitor survey in order to test how close AI might be to taking over my job. The survey was designed to assess the community impact of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate (“The Bean”) in Chicago. The result wasn’t a survey instrument that I would ever design, but it wasn’t entirely outrageous, either.

Some questions that ChatGPT generated were interesting, but what I found awkward about this “brainstorm” (or “webstorm”?) was that I didn’t know how to engage with the results. If a colleague or client had drafted these questions, I would have interrogated them to understand where the questions were coming from and what they were trying to get at. It could well be that the colleague knows something about the local community or the artwork that would convince me to adopt their suggestions. But with AI, questioning the intentions behind the text is pointless. You can ask ChatGPT why it produced a certain output, and it will create an elaborate justification, but it’s entirely fabricated. The output didn’t result from a human thought process, so there’s really nothing for it to explain (that would make sense in human terms). It does nothing to establish trust or convince me to accept the AI’s suggestion as superior to my own. Something essential is missing that prevents true communication.

Not long after our little ChatGPT experiment, I came across the following description of Donald Davidson’s idea of radical interpretation: “To make sense of [language], a listener must begin with a stance of good faith by assuming that the person they’re listening to has rational beliefs and is making meaning. This must happen before the listener can begin to interpret what that meaning is and whether she agrees with it.” That quote helped me put my finger on what was missing in my AI exchange, but the emphasis on “good faith” as a necessary starting point for communication also made me question whether that’s lacking in human-to-human communication these days as well.

I’m not fundamentally opposed to AI. In fact, I’m excited to see how it can help researchers, in particular, with summarizing and analyzing qualitative data that is currently underutilized. However, as we navigate the transition to an AI-enhanced world, I find myself (re-)considering my basic assumptions about the relationship between knowledge, community, and communication.

2026: The Year of the Connector

By Erin Gold, Consultant

As we begin to say goodbye to this year, I find myself, like most years, reflecting on the research we’ve conducted and the data we’ve gathered over the past twelve months. And of all the interesting findings and conversations I’ve been privy to, one idea that I keep coming back to is: What if arts organizations stopped thinking of themselves solely as presenters and instead began imagining themselves as facilitators of social connection?

We know from years of survey data that audience members use the arts to connect with others—especially their friends. Regardless of age, relationship status, or income level, there is a significant subset of people (those we call “social initiators”) who enjoy inviting and attending arts events and performances with their friends. While the data is crystal clear on this point, it reflects my own personal experience as an arts goer. Since moving to Madison, Wisconsin, I’ve relied on the city’s arts and cultural offerings—museum exhibitions, theatre performances, musical concerts—as a way to connect with and make new friends. These experiences have not only given us something to do together, but also something to talk about and build on—conversations that might otherwise never occur. And yet, without my inviting those new friends to come along, these moments of connection likely wouldn’t have happened at all.

Our recent Membership & Affiliation Survey found that a substantial proportion of respondents say they would attend more often if they had a group of friends to go with them. The data reflects a real desire to interact—not only with close friends, but also with acquaintances and even strangers encountered at arts events. And yet, we see relatively few social programs designed to encourage and support this behavior. Those social groups we have encountered in our research are naturally occurring and not formally affiliated with any arts organization.

This leads me to wonder how much demand remains dormant simply from a lack of social stimulus. This latest survey data suggests quite a bit. At a time when half of American adults are reporting feeling lonely and lacking companionship, what might it look like for arts organizations to play a more intentional role in facilitating social connection?

As I tidy up my desk and prepare for what the new year might bring, I’m keeping one sticky note posted above my monitor: “You’re not just presenters; you are facilitators of social connection.” I first wrote it as a provocation, something to mull over. Now, I keep it as a reminder of what I hope all of us in the arts might work toward in the coming year.

Hope for the Future

By Steven Holochwost, Principal and Director of Research for Youth & Families

December 2008 was my one-year anniversary with WolfBrown. Dennie, Tom, and Alan commemorated the occasion by sending a blanket for our newborn son, Jonas. That was the first Christmas that we spent as a family of three. December 2025 marks my 18th anniversary with WolfBrown, and the last Christmas that Jonas will spend with us as a full-time member of our household before he departs for college next fall. To say that the intervening years went through vast change is a tremendous understatement: it does not seem possible that the adorably helpless baby I held in that blanket could be the same person that I now have to stand on tiptoes to look in the eye. (To state that this diminishes my parental authority is also a great understatement.)

As Tom notes in his piece, 2025 feels like a more precarious and even troubled time than 1983 (a time I do not remember), and it certainly feels to me like a less hopeful time than 2008, which I remember clearly. And yet now, as then, the ordinary magic of children’s development, as the young people of today become the adults of tomorrow. My interactions with young people—both personal, through my sons and their friends, and professional, through nearly 20 years of work with WolfBrown—have led me to believe that the youth of today will be able to meet the challenges of tomorrow. Even in these times, I take great hope in that.

Multiplying Bills

By Dennie Palmer Wolf, Principal Researcher

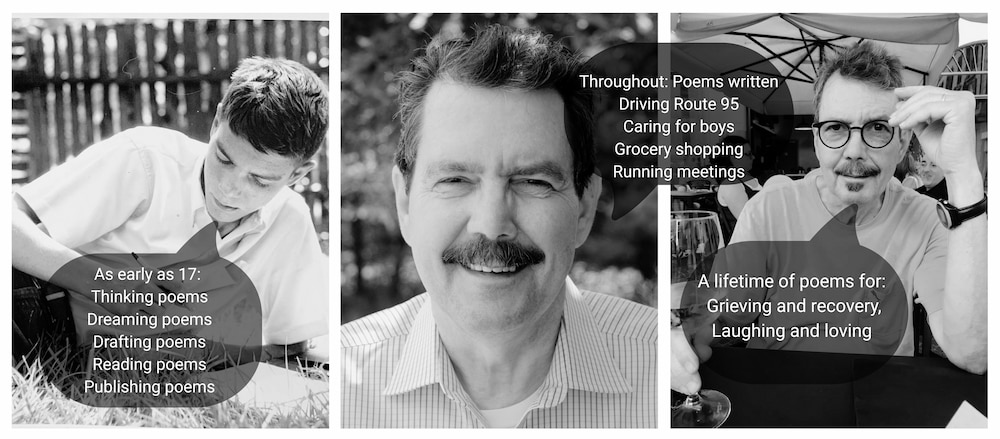

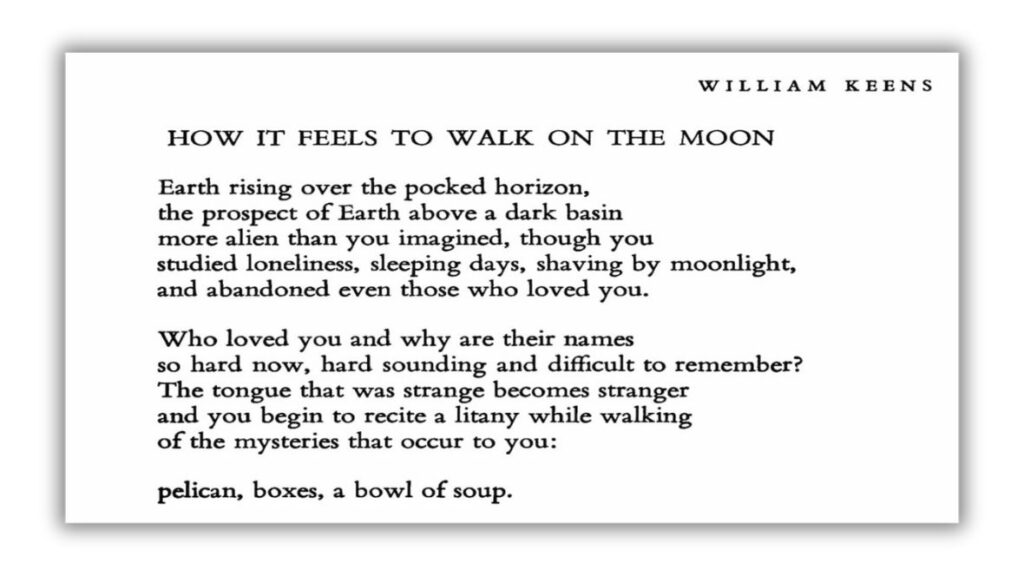

This year witnessed a sad transition: the passing of Bill Keens after a years-long duel with Parkinson’s. Bill was a mighty figure at WolfBrown: an early and long-running partner, a moral and artistic compass, and a long-standing example of a life continuously shaped by an engagement with the arts. In his earliest days as a poet, he published poems, won the Randall Jarrell Creative Writing Scholarship, and graduated from the Iowa Writers Workshop. As life wound on, he became a strategist, facilitator, and writer helping countless cultural organizations realize their missions. But poetry was always there, an underlying pulse, surfacing to articulate life’s large and complicated events.

Once, when our family experienced a tragic and unexpected death, Bill traveled to the memorial, bringing not only his generous presence but a just-written poem that spoke to the shock of sudden grief and the slowly-emerging possibility of memories as large as the loss. Years later, on my birthday, when his hands already shook uncontrollably, he etched out, letter by broken letter, the handsomest wish I have ever received, and placed it inside a book whose imagery, when read aloud, gave him pleasure, even as his own writing was no longer physically possible. Since, I have read his love poems to his wife, Caroline, each and every one leaving me sure, “Now that is what it is to be beloved.”

His transition from life to remembered life has made me think, almost daily, about people whose lives continue in artistry, even as they earn their bread, pay their bills, or fill in forms as something different: receptionist, medical technician, or data analyst. I think about the people who sing – or craft furniture – or write poems – quite seriously – their bodies and spirits filling in a way their emails, invoices, inspections, or meeting agendas never spark. In those “off hours,” they know how to soar.

For me, this points to a different kind of transition: So much of our work in arts and culture focuses on either audiences or full-on artists, ignoring people who live in this middle ground: the people, like Bill, who are artist-on-the-side-but-no-less-accomplished and passionate. If we would pause, we would realize that they are mighty beacons and multipliers – their lives broadcast what writing, singing, playing the banjo, or making beautifully crafted objects mean to a life well-lived. We would recognize how they bring audiences into concert halls, pass those values onto children and grandchildren, wake up co-workers to wonder about using early mornings or overtime in active and creative ways. What if we urged institutions, city governments, and foundations to invest in the Bills of this world: Asking:

- Symphony orchestras to sponsor play-ins for accomplished musicians-on-the-side

- Foundations to fund organizations that welcome and support opportunities in this middle ground

- Arts organization to create prizes and fellowships for elders who have lived long lives as remarkable, “sometimes” artists and deserve the time to flourish in their practice – even if just for a while.

In short, this is an invitation to all of us to wonder about how we might recognize, acknowledge, and multiply the Bills in our world – people who remind us, during our ordinary days, to imagine how it feels to walk on the moon.

How One Granny Square Changed Everything

By Surale Phillips, Principal

“We view creativity as a public good that is essential to the social good because it helps us imagine alternative futures, fuels empathy and connection, drives civic engagement, and creates adaptable and resilient individuals and communities.” — Steven J. Tepper and Terence E. McDonnell

It started with one granny square at Upcycle Day at Resource Depot, a creative reuse center in West Palm Beach. Five of us sat nervously around a table as our instructor—a young, tattooed woman with vibrant green hair—guided our amateur hands through the loops and pulls of crochet. Our conversation revealed she’s a costume designer at the theatre I regularly attend. Being thirty years her senior, it was a connection I never would have made otherwise—creativity had opened a door between our worlds.

What began as learning one granny square has blossomed into a daily creative practice. After every workday, I pick up my hook and yarn, and for a peaceful hour, the world narrows to just the rhythm of my hands. This simple act brings me joy and calm. It’s given me the gift of giving—handmade scarves, hats, and blankets for my community.

But the most surprising gift has been connection. On a train recently, I was crocheting hats for my granddaughters. The woman beside me asked, “What are you making?” Suddenly, we were sharing memories and talking about our families. Creativity had created a bridge between us, transforming a silent commute into a meaningful human exchange.

Now, several months in, friends bring me supplies and ask about my projects. Creativity of any kind can be transformational, especially as a daily habit. It hasn’t just enriched my inner life, it’s woven new threads of connection through my entire community. All from one granny square and a willingness to learn something new.

This change has connected me more deeply to Resource Depot’s mission. I shop there more. I attend events more. I donate more. “Every day, Resource Depot encourages others to have fun with diverse materials, inspiring children and adults to express themselves through creating.”

I’m hooked. Pun intended.

Two Becomes One

By Claire Pavlik Purgus, Office Administrator and Bookkeeper

At WolfBrown, “field learning is our passion.” We engage with our clients on the ground, in their arts programs, and seek to understand their complex weave of experiences, perspectives, and challenges so we can better support their missions.

As a passion, field learning at WolfBrown is not restricted to one’s professional life, but extends to each of us personally. This month, I was granted leave to immerse myself in Indian culture and gather with family. My niece, who hails from the tiny island nation of Mauritius, was getting married to a nice Indian boy.

The wedding was the culmination of a year of planning, which tied my niece’s nerves like fringe on a shawl. Dare I wonder if she was nervous about this next chapter of her life? She’d been a staunch daddy’s girl, and soon he’d give her away.

If she was apprehensive, she didn’t show it. The three days of wedding festivities were a vibrant blend of traditional ceremonies and style, drawing on Kannada, Punjabi, and Mauritian cultural customs. (Culture is plural!) I’m sure she wanted everything to go smoothly, and it did.

Weddings join two people in holy matrimony, and two families become one. It is a joyful occasion that doesn’t subtract one from two, but adds one plus one to equal one.

With the joy, there is grief, too, like jaggery and bitter gourd. The well-loved daughter, now a proud and happy bride, is given unto the groom and his family for safekeeping; and the little girl who once was no longer scampers through the rooms of her father’s house.

Horses, Buggies, and the Future of Arts Consulting

By Dr. Thomas Wolf, Principal

Any idea what year the following events happened?

- The ARPANET officially changes to using the Internet Protocol, creating the Internet.

- Compact Discs and players are released for the first time in the United States and other markets. They had previously been available only in Japan.

- Two American astronauts perform the first space shuttle spacewalk.

- Astronaut Sally Ride becomes the first American woman in space.

- Bill Gates introduces Windows 1.0

- The AT&T Bell System is broken up by the United States Government.

The year was 1983, an important one for our firm as we opened our doors that fall. Our first contract was with a greatly expanding National Endowment for the Arts. The Chairman was interested in conducting a comprehensive study of arts education in the US in anticipation of creating a new initiative. Despite President Ronald Reagan’s threats to cut the NEA’s budget, strong bipartisan support for the agency saw it grow by 13 percent the following year. The future looked bright.

We live in a very different world today. Despite all of the technological advances, despite the creation of countless new arts organizations, and despite the expansion of resources in support of the arts—both public and private—many things about our field seem precarious today. Some challenges often feel insurmountable. But I am convinced that the need for the kind of work we do at WolfBrown has never been greater.