A Series of Case Studies from Effective Leadership for Nonprofit Organizations

After many years of consulting, I came across a persistent problem in many organizations. Executive directors and boards often struggled to understand the dynamics of their relationships. Sometimes the board would steam roll the executive director, asserting the legal authority of trustees. In other cases, strong executive directors would side-step the board, making unilateral decisions with little or no consultation. This led to my writing of a book attempting to define the ideal relationship between boards and executive directors—I call it the “magic partnership” as outlined in the graphic below.

– Dr. Thomas Wolf

The following cases outline some of the dynamics of the magic, ideal relationship between boards and executive directors.

2. Getting the Board to Fundraise

Getting the Board to Give

This is a case histories that shows how an executive director and a board member worked in concert to effect more robust giving in a small nonprofit.

– Dr. Thomas Wolf

Tom was in his mid-twenties and still in graduate school when he was invited to serve on his first board. The board he ended up joining was connected to a small, separately incorporated, local chapter of a national nonprofit coalition. His mother had served on the national board with distinction for many years, and she had been quite a colorful and beloved member. When one of the chapters learned that her son lived in the area, they immediately asked him to join the local board. After receiving the invitation, he called his mother to ask whether it was appropriate to accept, given his limited time availability and even more limited trustee experience. She said. “You should do it. I have heard they need you.”

Once Tom attended his first board meeting, he realized his mother had not been exaggerating; he might be of some assistance to a hard-working executive director who had to struggle with a rather inactive board. Tom met with her privately to learn about the organization and received an earful of complaints about problems, especially in the financial area. Despite the impressive list of board members and the obvious wealth of some of them, the organization’s finances were in a shambles. And it was clear why. The trustees were not giving much money—indeed, some gave nothing at all.

“Give, Get, or Get Off.” That much, at least, Tom had learned from his parents and he had already put aside money to contribute. He accepted the board assignment knowing that trustees need to donate, they need to raise money, and if they don’t do these things, they need to get off the board and make room for others who will. He remembered the argument. The board should be the first line of support. They need to set the standard of giving, and then they must go out and raise more. Well, it certainly wasn’t happening in this organization.

What to do? Tom had no idea. The executive director spoke confidentially and frankly to him. “My dilemma,” she said, “is that I am the wrong one to complain. I can’t tell the board members they should be giving more. It has to come from the board itself. But no one is willing to tackle the issue, not even the president who, compared to the others, is rather generous. I need help from someone, and if you are willing, I can coach you on what to say.”

Tom and the executive director waited for an appropriate opportunity to inject the issue into a board discussion in a natural and unforced way. That opportunity was a discussion of the budget for the coming year. There was much hand wringing about how difficult it was going to be to balance the budget, given how little money had come in. Tom raised his hand. “How much of the individual contributions are coming from the trustees?”

The question was not spontaneous. It had been planted by prior agreement between Tom and the executive director, so an answer was immediately forthcoming by her: it was a paltry sum that trustees contributed. “My,” Tom said (again well prepared). “That’s a very small number. How many of us are giving?” When told that only about half the trustees were donors, Tom tried to look shocked. “Well, I know I am the youngest one here, and I should probably defer to others. But people I respect a lot have told me that in nonprofit organizations, all trustees should be contributing something.”

After an awkward silence, the meeting moved on. But Tom wouldn’t leave it there. The next day, he wrote a letter to his fellow trustees saying that he had rechecked with a friend who worked at a foundation, and he had been informed that most foundations would not consider a grant application from an organization unless there was 100 percent trustee participation in giving. “So let’s set ourselves a modest goal this year of 100 percent participation by the trustees in giving and a $10,000 total from the board. Give what you can. But since there are twenty-five of us, you can figure out what we need to average per gift.”

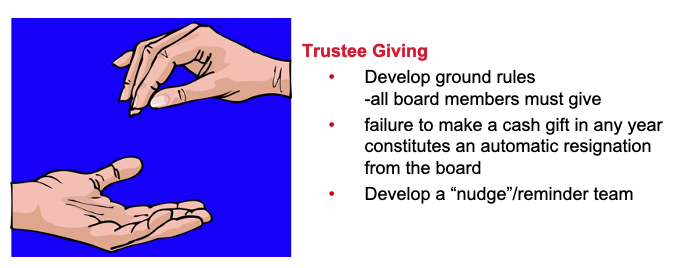

Gifts started coming in—some a lot larger than the $400 average that was needed. One trustee sent $500 and wondered whether she should resign, given that she couldn’t afford what she said was “the full $4,000 average gift.” Clearly her math skills were not very good, and Tom assured her that as she had in fact exceeded the average, there was no need to resign. After a week, Tom called those he had not heard from and in one case went to someone’s home in the evening to pick up the check. In the end, the money taken in was almost double what he had set out to raise. In addition, there were three resignations from the board (which Tom and the executive director privately celebrated), and there was 100 percent giving from the rest. The organization then enacted a policy stating that for trustees, failure to make a cash gift in any year constituted an automatic resignation from the board.

Getting the Board to Fundraise

This is a second case history that shows how an executive director can entice board members to be involved in the fundraising effort.

– Dr. Thomas Wolf

Some years ago, Jeanne, an experienced fundraiser and inspirational speaker, was invited to lead a conference seminar for executive directors on the topic of encouraging board members to fundraise. She was initially surprised by the invitation and cool to the subject matter. “This is not a good topic,” she told the conference organizer. “Getting board members to fundraise is not the executive director’s job. It is the job of the board president or other trustees. They have to light the fire and get their peers to be involved in the important work of fundraising.”

The conference organizer disagreed, saying, “You know perfectly well that in many cases it will only happen if executive directors become involved. Help them figure out what specifically executive directors can and should do.”

Eventually Jeanne designed a seminar under the title of this chapter: “Cracking the Whip: Getting Board Members to Fundraise.” To get good material in advance, Jeanne canvassed participants, asking a simple question: “What excuses do board members give for not fundraising?” The various responses were placed in a dozen categories that were dispiritingly familiar:

1. I don’t know how to ask for money.

2. I don’t feel comfortable asking for money.

3. Others are better at asking for money than I am.

4. I can’t ask my friends for money.

5. I can’t ask my family for money.

6. If I ask people for money, they will ask me.

7. I already gave.

8. I am too busy.

9. The executive director is a professional in this area.

10. The organization already has development staff.

11. I do other things for the organization.

12. I won’t be successful.

Having seen the many manifestations of the problem, Jeanne was able to get participants to come up with common sense solutions to how they could be addressed. Many of the executive directors were already using one or two of them, but collectively, they amounted to a veritable arsenal of strategies.

Let’s start with the heart of the matter—the concern about asking for money. The first six of the twelve reasons for not fundraising all have the word “ask” in them. So clearly, many trustees simply do not understand the comprehensive nature of the fundraising process of which asking is just one part. They hear the term “fundraise” and it conjures up a picture of a bejeweled matron or a corporate titan sitting impatiently, drumming the arm of a chair while the reluctant trustee begs for a handout. It is a frightening image for many trustees, especially those who have never thought about it before, so the first task is to dispel the image. The second is to replace it with a comprehensive picture of the fundraising process. That is an executive director’s role.

As one executive director put it, “We have analyzed all the tasks that go into fundraising at our organization. Yes, making calls and asking someone for a gift is one job. But there are so many others: working on our annual gala, or other fundraising events, is one large category. Personalizing direct mail letters and personally acknowledging gifts by writing thank you notes is another category (some of our younger trustees will send out emails). We also encourage our trustees to go through annual reports and programs of other local nonprofits and compile lists of their high-end donors and then secure addresses when possible so we can add them to our prospect list. Identifying acquaintances or family members who might be associated with corporations and foundations, working on a fundraising video, taking photographs at some of our programs that could be included in a brochure, helping to develop good ideas and copy for fundraising materials—the list goes on and on. Any of this can be counted toward discharging one’s fundraising responsibilities.”

“What we do is ask board members to rate these activities in order of preference. Once they do, we are well on our way toward developing an army of fundraising volunteers. We find that there are a lot of things that are part of fundraising that even our most recalcitrant volunteers are willing to do. And success in one area can often build confidence in another. You would be surprised by how many of those who absolutely refused to ask for money are now comfortable doing so. It is my job as executive director (and that of my development director) to work with the group, finding their areas of interest and willingness and nurturing them.”

Once trustees have chosen fundraising tasks, there is still the challenge of fulfillment. Many will sign up for things with the best will in the world and then discover they are too busy and put off the responsibility. Addressing this frustration can be as easy as developing written assignments with due dates and a master calendar that is shared with the entire board. Once again, it is the executive director who either performs this task, or in larger organizations with development staff, ensures that it gets done. Monitoring, reminding, and reporting is as important as developing the assignment sheets in the first place.

It remains the case that some board members will actually have to do some soliciting, and here the issue may be fear of the unknown and fear of failure. Looking at the list from Jeanne’s workshop, many of the excuses board members gave centered around anxiety about the act of asking. Change that and one is more likely to get volunteer askers.

A skilled executive director can begin the process of addressing the anxiety of asking by breaking it into finer grain detail. What are people really worried about? As it turns out, in example after example, there are five important anxiety moments that trustees talk about:

- The first is the moment of setting up a fundraising appointment. What should they say and not say? How much should they acknowledge about it being a fundraising call? Would they get rejected before they even get an appointment?

- Second, there is the worry about how to start the conversation once they meet with a prospect. What should they talk about?

- Third is the moment of making the transition to the topic of fundraising. There can be great anxiety about doing that smoothly and without embarrassment.

- Fourth is the ask itself. Should they ask for a specific amount? Would the donor be insulted or angry if they did?

- Finally, there is the anxiety of knowing what to do when they get an answer, especially if that answer is no.

Helping trustees feel more confident about each of these anxiety moments can go a long way toward making them willing to try. Practicing with them might well give them the confidence they need to get over the hump. Accompanying them on some initial calls will provide practice and even more confidence.

An executive director, especially one who is not particularly confident and experienced about these issues, may want to solicit help from a board member or an outside professional trainer. Or he or she may decide to pair less-experienced trustees with confident, experienced ones (or with a staff member). No board members should be forced to solicit friends or family if they do not want to, though all should be encouraged to serve as door openers for others. Since nothing succeeds like success, and the greatest inducement to persuading trustees to do more fundraising is to have them succeed the first few times, it is important to collect and disseminate success stories. Offering beginners low hanging fruit to help them succeed on their initial forays can also serve as an encouragement device.

One of the most important misunderstandings is found in organizations that have professional development staff or even in those where the executive director is the only professional who raises money. Some inexperienced trustees, recognizing the expertise and competence of these individuals, may wonder what they can offer in fundraising. For starters, as we have seen, there are many tasks that do not require expertise. And there are others where the involvement of a board member is simply more appropriate. As volunteers, who are themselves giving time and money, their credibility may well be greater than salaried staff. In addition, their involvement in an ask can serve as a compliment to a potential donor.

Again, it is the executive director who can help convey these messages, explaining what development staff members actually do and where they need help. Explaining the credibility that board members bring to the fundraising process puts the proposition of their involvement in the form of a compliment rather than a scold. It also builds a sense of teamwork that provides a strong and positive culture within the organization.

Jeanne’s “Cracking the Whip” conference seminar was so popular that many other groups requested it and she repeated it many times. Eventually, she built the topic into a fundraising course she taught at a local university. The topic of how an executive director can encourage board members to fundraise turned out to be an important one and served as another example of how an effective executive director can help individuals become more effective trustees.

–© Thomas Wolf from Effective Leadership for Nonprofit Organizations: How Executive Directors and Boards Work Together, Allworth Press, 2013. Buy the book.

We have more case studies on our website.

Part 1 focuses on evaluation, coaching, and balance of power.

Part 3 focuses on dealing with bad news, organizing meetings, and being a good board president.