By Alan Brown

The journey towards a more equitable future for nonprofit arts organizations starts in the boardroom and too often ends there, as well. This issue of On Our Minds, the second in a series examining more equitable practices, reflects openly and self-critically on the underlying processes, assumptions, and structures driving strategic planning and what would make them more equitable.

Any talk of reform must begin with an acknowledgment that, as consultants hired to lead planning processes, we are often complicit with our clients in reinforcing organizational norms and structures that perpetuate inequities:

- shying away from difficult conversations;

- not challenging underlying assumptions and beliefs;

- not bringing enough diverse perspectives to the table;

- not challenging donors who wield undue influence; and

- agreeing to planning approaches that do not tolerate a plurality of viewpoints on future directions.

While there is a world of criticism to heap on strategic planning as an organizational practice, we hope to shine a light on some concrete ideas for improving it. What models and frameworks for planning would help boards come to grips with conflicting value systems around equity? How can planning processes center diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging? How is equity instilled organization-wide as a core value?

We are committed to working with funders, organization leaders, and other consultants to design better planning processes that propel us toward a more equitable future.

Contributions

- Centering Democracy in Strategic Planning: Alan Brown discusses how centering cultural democracy in artistic organizations’ work might lead to equity in strategic planning.

- Equity and Strategic Planning: An Interview with Stanford Thompson: Dr. Thomas Wolf interviews a long-time collaborator on the topic of equitable strategic planning.

- Walking the Equity Walk: Joseph H. Kluger considers how organizations might use core values to support attaining goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Centering Democracy in Strategic Planning

By Alan Brown

More than ever, now is the time to reconsider how we plan for the future and what skills and approaches are needed to manage change.

A moral imperative to move towards a more democratic and less racist cultural sector has taken root in the hearts and minds of many board members and executive leaders. However, questions about how to operationalize this commitment at the institutional level often go unresolved. Not everyone feels the same urgency about resolving them, and emotions run high. Equity lives as an empty promise until it is manifest in the systems and policies that shape the future of our institutions and communities, starting with strategic planning.

As the massive injection of Shuttered Venues and other “relief” money wends its way through the digestive tract of the sector, one wonders if cultural organizations will, in fact, emerge “relieved” in some fashion – i.e., trimmed to a sustainable size – or simply more dependent on relief money.

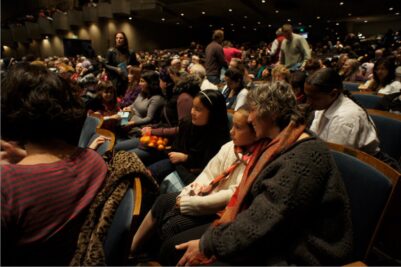

Recovering from the pandemic is more complex than wooing audiences back to the theater, as many organizations are learning. The more fundamental crisis of relevance brought on by accelerating changes in the operating environment during the pandemic has exposed our inability or unwillingness to change with them. Public tastes in art have changed. The opportunity cost of going out has risen. Consumers have grown more adept with a range of technologies. Will we double down on the very structures that caused the crisis in relevance that we now find ourselves in, or can we evolve intentionally and methodically?

All told, many find themselves in an awkward position of knowing that meaningful change is necessary while, at the same time, lacking a clear vision of what that change looks like or what sort of planning process will bring a new vision into view.

The Way We Plan Must Change

During the pandemic, we learned about scenario planning as a way to manage uncertainty. Hopefully, we learned that planning is not an episodic process that happens once every few years but a continual process that allows for rapid adaptation based on changing circumstances. In times of crisis, looking beyond the short term is challenging. But long-term vision and strategy take on even greater importance during periods of significant stress.

The great irony of strategic planning is that real strategy is seldom discussed because the status quo is tacitly understood as the only way forward. Many board members are uncomfortable debating institutional strategy. Thus, strategic plans tend to trim around the programmatic edges or make bold statements about innovation or equity but avoid addressing difficult questions of why we do what we do, who we exist to serve and what it means to be place-based, what range of artistic experiences we are and aren’t willing to present, what trade-offs we are and aren’t ready to make to serve a broader audience, and how we manage risk and protect what’s important to us with capital. Taken together, this is an institutional strategy. And reasonable people can disagree on strategy because it is, fundamentally, a creative thought process.

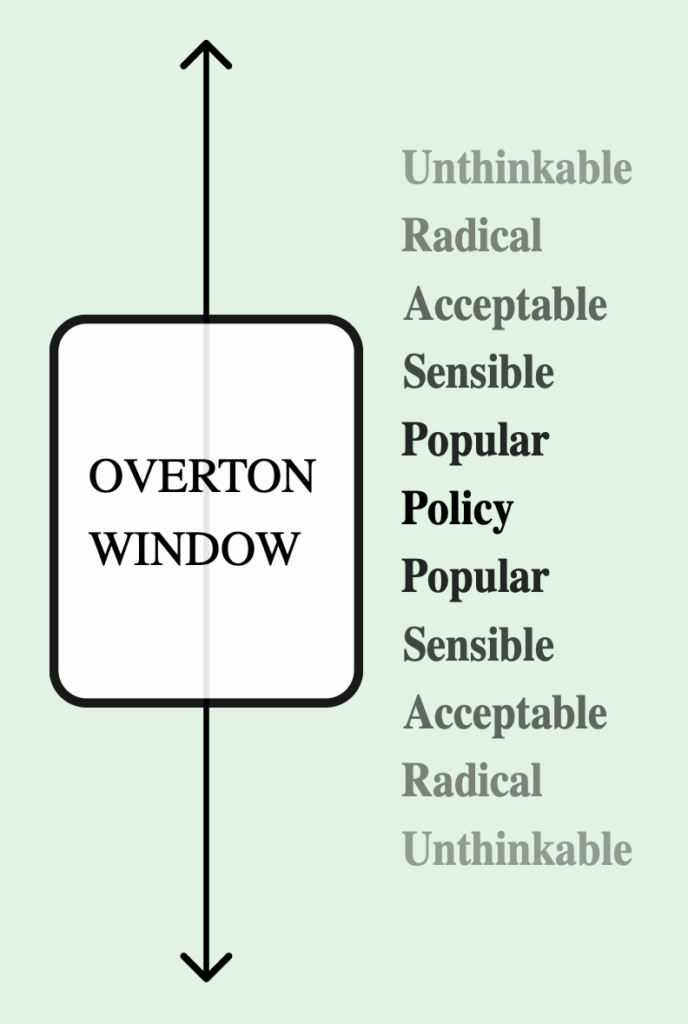

Regrettably, most strategic planning processes do not tolerate debate and discussion of multiple visions for the future. Too much is invested in the status quo to entertain other pathways forward. I was foolish enough some years ago to ask a room full of board members and senior staff, “What could you be if you started over?” That didn’t go well. Financial distress flings open the Overton window, but it shuts just as fast when a donor plugs the gap. Surely there are better approaches to strategic planning that allow organizations to make informed and intentional decisions to renew and refashion themselves – while they’re still healthy and not facing bankruptcy or wholesale downsizing. Some funders have established grant programs for organizations seeking transformational change. Still, it will take much more than the promise of a planning grant to draw large institutions into an equity-centered planning process. I do want to credit the OF/BY/FOR ALL organization and its Change Network for their leadership in establishing structures and value systems that promote community-centered planning work.

How Can Equity be Centered in Strategic Planning?

In many ways, how you go about the planning work pre-determines the outcome. If you ask a consultant to create a three-year plan based on the last three-year plan, you’ll likely get a derivative plan with minor changes in emphasis. Suppose you start a planning process by asking your artistic director for their 10-year artistic vision. In that case, all talk of programmatic strategy is foreclosed, and the planning work will naturally center around marketing and fundraising. If you instruct your planning consultant to prioritize equity, diversity, and inclusion in the planning process, you’ll get a pillar in your plan that prioritizes DEI. I see this in strategic plans all the time now, and it often takes the form of an unfunded mandate.

What would a strategic planning process look like that centers equity? Lots of consultations with external stakeholders? As a consultant, I’m faced with the dilemma of figuring out how to design planning work that foregrounds issues of equity in organizations whose board members are not fully committed to the idea of equity or are even hostile to it. While I would love to see equity at the heart of every planning process, this would require a capacity for critical self-reflection at the board level that is not always there. In my experience, talk of equity and the underlying structures that perpetuate bias of all kinds can be difficult for some board members. I was asked, “Why are we having this conversation? We’re not a social service organization!”

In his 2021 book, “Audience Development and Cultural Policy,” Steven Hadley, the British researcher and arts consultant, argues that 20+ years of social inclusion work hasn’t fundamentally changed the demographic complexion of the ticket-buying audience for western-based art forms. He contrasts these efforts to “democratize high culture” with the movement towards “cultural democracy,” which equally values all forms of cultural expression.

The tension between “democratizing high culture” and “cultural democracy” nicely encapsulates the conflicting value systems within many arts organizations and could be a helpful framework for strategic planning. In other words, the planning work would seek to reconcile two questions:

1. “How can we open up our art to a more diverse public?”

2. “What can we contribute to a more democratic culture?”

An organization’s answers to these questions will position it along a continuum from inclusion to equity, clarify the many steps along the way, and highlight differences between commitment in policy and practice. This reconciliation process offers a means of surfacing and interrogating basic assumptions about institutional identity and intended impact – the foundation of strategic planning.

What Does Success Look Like?

Surely every arts organization has something to contribute to a more democratic culture. In fact, many are already well down this path.

- Would a commitment to cultural democracy allow an orchestra to have a resident jazz ensemble? Or a resident flamenco ensemble?

- Would a commitment to cultural democracy lead an opera company to not only lift up operatic voices but also other kinds of voices?

- Would a dance company’s commitment to cultural democracy lead it to host community dances, where professional dancers mix with aspiring dancers of all ages?

- Would a commitment to cultural democracy lead a performing arts center to open an immersive restaurant as a platform for engaging the community in learning about cultural traditions from around the world?

- Would a museum’s commitment to cultural democracy lead it to teach youth and adults to curate exhibitions in their homes and community spaces?

Is there room for the idea of cultural democracy in our biggest and slowest-to-change institutions – not just in the education department but also on the main stage and, in fact, in the boardroom? All I know for sure is that some of the most talented artists, artistic directors, and curators in the field are excited about bringing these two value systems closer to their core programming.

A Call to Action

In sum, we need better models and frameworks for strategic planning that reflect the uncertainties of the marketplace, challenge core assumptions, tolerate consideration of multiple pathways forward, and bring board members and staff into a rich dialogue about what the arts can contribute to a more democratic culture. In this way, strategic planning is both an opportunity for equity training at the board level and also a means of incrementally progressing down the long road toward a more equitable sector.

And then, consider what might happen if multiple organizations in the same community start sharing their thinking about cultural democracy and working together towards a shared vision at the community level.

If there is one practical change to make around strategic planning, I would like to see a pre-planning or “plan to plan” exercise done by a third-party consultant who is not a candidate to do the eventual planning work. This exercise would bring a level of impartial, critical thinking to the planning process itself and help guide institutional leaders towards a process (and a consultant) that is best suited for their needs.

Finally, consultants and funders must work together to build more robust support systems for boards and executive leaders. We need to make long-term investments in the capabilities of community leaders who serve on boards so that more are comfortable discussing equity and finding a voice in strategic planning matters. After all, the vision is theirs to hold. A vote by a board of directors to submit their organization to a process of transformational change should not be seen as a last resort but as a bold act of leadership.

This is piece is part of our series on equity and strategic planning. You can read other posts here:

- Equity and Strategic Planning: An Interview with Stanford Thompson: Dr. Thomas Wolf interviews a long-time collaborator on the topic of equitable strategic planning.

- Walking the Equity Walk: Joseph H. Kluger considers how organizations might use core values to support attaining goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion.